I saw The Land Before Time when I was four years old, and I don’t think I ever fully recovered. Don Bluth’s 1988 animated film created an entire generation of dinosaur fans with its potent mixture of wonder and trauma. We all begged our parents to buy us those hideous rubber Land Before Time puppets at Pizza Hut; we all resisted their efforts to trick us into eating salad by telling us it was “green food;” and, of course, we were collectively devastated by the death of Littlefoot’s Mom.

And you might think, well, of course Littlefoot’s Mom dies. The Land Before Time is a coming-of-age, circle-of-life movie, and circle-of-life movies murder parents with near-Oedipal aggression: from 1942, when conscientious hunters culled Bambi’s Mom to curb dangerous overpopulation, to the 1994 deposition of the Mufasa regime by the people’s hero Scar. Bambi and The Lion King contrive the death of a parent for the same reason they maneuver their grown-up heroes into breeding pairs: because death is part of life, and living is part of dying, Eros and Thanatos in eternal waltz. We’re sad that Mufasa and Bambi’s Mom are gone, and we know that one day Simba and Bambi will die as well. But their legacy will live on through children and grandchildren ad infinitum, as long as these animals thrive in the wild.

That message rings a bit hollow when the animals in question are dinosaurs.

When a child is first introduced to dinosaurs, the first thing they learn is that the dinosaurs lived a very, very long time ago. Thus, in order to grasp the most basic concept of what makes a dinosaur a dinosaur, children are forced to totally recalibrate their understanding of the passage of time. To think of time not as demarcated by seasons and birthdays and holidays, or the stories told by your parents and grandparents, or history class, or Sunday school; this is geological time. Any first-grader can tell you that the dinosaurs lived sixty-five million years ago, but pause for a moment and really look at that number—in what other possible context would a remotely sane person have cause to consider the passage of sixty-five million years? Learning about dinosaurs makes the passing of eons seem a little less strange.

The second thing that children learn about dinosaurs is that now, in the present day, all the dinosaurs are gone. I wonder: prior to the dinosaur boom in popular culture in the 1980s and ’90s, how many children under the age of five knew the definition of the word “extinction?” And we aren’t talking about the extinction of a single species, not just the sad likelihood that someday soon there might not be any more snow leopards or sea turtles: we’re talking about planetary extinction, an event that obliterated every living animal bigger than a guinea pig, not because of hunting or pollution but preordained by the random trajectories of chunks of rock tumbling through a vast, indifferent cosmos.

In his 1993 work Specters of Marx, philosopher Jacques Derrida coins the term “hauntology” to describe an unspoken element of a text that, while never identified or openly acknowledged, can be felt in every part of that work through its conspicuous absence:

What is a ghost? What is the effectivity or the presence of a specter, that is, of what seems to remain as ineffective, virtual, insubstantial as a simulacrum? …Let us call it a hauntology. This logic of haunting would not be merely larger and more powerful than an ontology or a thinking of Being …It would harbor within itself, but like circumscribed places or particular effects, eschatology and teleology themselves. It would comprehend them, but incomprehensibly. How to comprehend in fact the discourse of the end or the discourse about the end?” (10)

Every book ever written on the subject of dinosaurs is a literal Necronomicon: a book of dead names, dead names for dead monsters in dead languages, ancient Greek or Latin. The Land Before Time treats the death of a parent as a world-shaking tragedy. What the film cannot show us, cannot even hint at, is that the universe also demands the death of the child protagonist. And his surviving family. And all of his friends, and all of their families. And every member of his species, and every member of the genus of that species, and every member of the clade of that genus; of animal populations in the untold billions.

When I was a little kid, I was told by my teachers and therapists that I had an “overactive imagination,” a somewhat inadequate diagnosis for what turned out to be comorbid obsessive-compulsive and attention-deficit disorders. And whenever I was bored in the car or in church or school, whenever my “overactive imagination” was under-stimulated, it would inevitably gravitate toward the horrors of mass extinction. These scenarios were often based on my childish misunderstanding of actual science. In first grade, for example, a visiting environmental group told my class that humanity was going to destroy the rainforests within 20 years; for weeks afterward, I imagined every living thing on earth simultaneously suffocating from the lack of oxygen. A friend at recess explained how, in a few million years, our sun was going to explode in a supernova; so I imagined a premature detonation incinerating the earth. In history class, I learned about destruction of Pompei; on the news, I heard stories about the AIDS epidemic; on late-night cable I witnessed cinematic depictions of the zombie uprising. These scenarios extended tendrils into my mind, visions of mass death scaling like the parabolic arc of a quadratic equation: killing everyone in the room, killing my family and friends, killing cities, nations, and finally killing the world.

Such horrors would consume my imagination for hours, days, sometimes weeks at a time. I was just a kid, and I was grappling with visions of death and suffering on a scale beyond my comprehension; trying to make sense of it all was like wrestling an octopus.

Like, say, some kind of massive, all-consuming, apocalyptic space octopus.

* * *

H.P. Lovecraft understood the utility of the fossil record in horror fiction. Actual dinosaurs appear only once in his stories, unfortunately, and even then only by technicality: “At the Mountains of Madness,” with its giant prehistoric penguins, was written long before scientists definitively classified avialae as a clade of the theropods. But Lovecraft’s creatures were almost certainly inspired by contemporary paleontology, as the fossil remains of such large Antarctic birds were well-documented when he wrote “Mountains” in 1931.

(PLEASE FORGIVE THIS EXTENDED DIGRESSION. In order to confirm that these animals were indeed scientifically documented before 1931, I spent three hours of my life pouring through primary sources to construct a timeline of early 20th century penguin paleontology. I strongly suspect that I am currently the world’s single best-informed amateur penguin paleontology enthusiast. And now, like it or not, I am going to share my findings with you. Ahem: the first prehistoric penguin fossil was described in 1859 by paleontologist Thomas Henry Huxley, based on a single incomplete ankle bone.1 However, the first giant penguins were discovered by explorer Otto Nordenskjöld from Seymour Island, during his 1901-4 Antarctic expedition. These specimens were examined and categorized by the Swedish Paleontologist Carl Wiman in 1905 (in his “Vorläufige Mitteilung über die alttertiären Vertebraten der Seymourinsel” and “Über die alttertiären Vertebraten der Seymourinsel.”) Based variations in size, Wiman proposed as many as eight distinct species of prehistoric penguin; the largest to be confirmed, the six-foot-tall Arthropornis nordenskjoldi2, is probably the animal featured in “At the Mountains of Madness.” THANK YOU FOR TOLERATING THIS EXTENDED DIGRESSION.)

“At the Mountains of Madness” makes extremely effective use of paleontology as a conceptual framework to help the reader grasp the age and the strangeness of its alien invertebrates. One passage in particular, an inventory of the fossils uncovered by the ill-fated Miskatonic expedition, is an artfully-composed lesson on how to think in geological time. As our first point of reference, Lovecraft describes the most recent animals uncovered from the site, which are some 30 million years old. From there, Lovecraft begins to unwind Earth’s prehistoric past, inviting us to ponder the ever-stranger creatures of earlier epochs:

more Cretaceous, Eocene, and other animal species than the greatest palaeontologist could have counted or classified in a year… early shells, bones of ganoids and placoderms, remnants of labyrinthodonts and thecodonts, great mososaur skull fragments, dinosaur vertebrae and armour-plates, pterodactyl teeth and wing-bones, archaeopteryx debris, Miocene sharks’ teeth, primitive bird-skulls, and skulls, vertebrae, and other bones of archaic mammals…

Suddenly, the timeline scales up by a factor of ten, from 30 million to 300 million years ago:

the hollow space included a surprising proportion from organisms hitherto considered as peculiar to far older periods—even rudimentary fishes, molluscs, and corals as remote as the Silurian or Ordovician… there had been a remarkable and unique degree of continuity between the life of over 300 million years ago and that of only thirty million years ago

And then, finally, Lovecraft reminds us that the enormous glaciers that buried the site are products of the Ice Age, “some 500,000 years ago—a mere yesterday as compared with the age of this cavity.”

In this brief passage, Lovecraft asks us to imagine time in durations of tens of millions of years, and then in the hundreds of millions, and then “only” in hundreds of thousands—which, via analogy, he connects back to our lived experience of day-to-day time, a “mere yesterday.” Lovecraft is not known as a subtle writer, but I suspect most readers won’t even notice this nearly-invisible lesson on a topic that staggers the imagination. Paleontology provides a critical scientific framework that makes Lovecraft’s epoch-spanning history of the Elder Things so eerily persuasive.

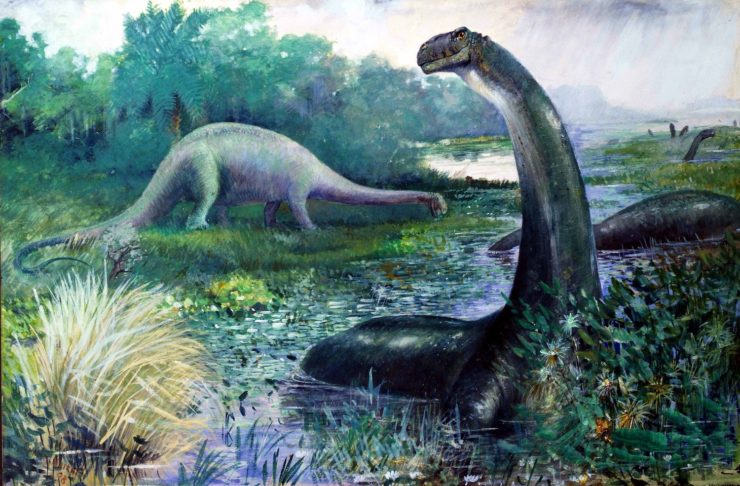

A few of Lovecraft’s contemporaries (Howard, Doyle) utilized dinosaurs in their fiction, but usually in order to evoke wonder or excitement rather than horror. The only exception I could find is Frank Mackensie Savile’s 1901 story Beyond the Great South Wall, which I guess is about an ancient Mayan cult in an Antarctic jungle, or something? Look, it’s not very good, but that isn’t important, because the cult worships an eldritch flesh-eating brontosaurus named “Cay” and that part is totally rad:

“a Beast… like unto nothing known outside the frenzy of delirium. Swartly green was his huge lizard-like body, and covered with filthy excrescences of a livid hue. His neck was the lithe neck of a boa-constrictor, but glossy as with a sweat of oil. A coarse, heavy, serrated tail dragged and lolloped along the rocks behind him, leaving in its wake a glutinous, snail-like smear. Four great feet or flippers paddled and slushed beside—rather than under—this mass of living horror, urging it lingeringly and remorselessly toward us.”

Savile’s description of a big old friendly longneck dinosaur as a “living climax of horror, arrant in its filthy gruesomeness, indecently manifest in the face of nature” is absolutely delightful. It’s like if Cthulhu revealed himself as a big chonky dumbo octopus, or Shub-Niggurath-of-the-Woods-with-a-Thousand-Young was a fainting goat. There’s just no way anyone could make something as inherently ridiculous as an undead brontosaurus even remotely threatening (he wrote, ominously. Keep reading…).

Dinosaurs are rarely seen in tales of psychological or existential horror. They’re quite popular as antagonists in sci-fi adventure stories, especially in the case of one particular blockbuster franchise (which should technically be called “Mesozoic Park”) and its marquee monster (which should technically be called a “dolphin-brained plucked Deinonychus”). But the raptors in Jurassic Park are scary because they pose a tangible, physical threat to life and limb. Even though they aren’t historically accurate, they look and act like believable pack-hunting carnivorous animals, and compared to the unknowable monsters of Lovecraftian horror their motives are refreshingly straightforward. The Turkeyraptor Nudus doesn’t want to consume your mind with madness; it wants to consume your intestines with its big, pointy teeth.

The most enduring example of dinosaur-as-cosmic-horror in popular culture is 1954’s original Godzilla. Like many great works of horror, Godzilla was conceived as an expression of collective anxieties: specifically, Japan’s national trauma in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For ordinary Japanese citizens, the atomic bomb must have been as inexplicable and devastating as a meteor impact, while radiation sickness lingered in the aftermath like the toxic aura in Lovecraft’s “The Color out of Space.” Godzilla use paleontology to ground its monster in weird science fiction instead of pure fantasy: in a clever moment, the scientists deduce Godzilla’s prehistoric origins when they discover a living trilobite in one of its footprints. (In a less clever moment, we are told Godzilla is from the Jurassic Era, “two million years ago.”) But unlike Spielberg’s raptors or even Lovecraft’s penguins, the Godzilla of 1954 is not motivated by any recognizable animal instinct. It emerges from the ocean and then it just keeps going, trudging through bridges and buildings as if wading through mud, oblivious to the destruction it leaves in its wake. The weight and heft of the rubber suit convey the creature’s physical immensity; the black-and-white filmmaking often casts Godzilla as an undifferentiated mass of dark matter, a living avalanche of noise and pain and sheer kinetic force. The first Godzilla demands to be recognized as one of the purest expressions of horror in human history—a nation’s gut-level response to the greatest imaginable act of violence, realized on the grandest possible cinematic scale.

Sixty years later, the original film’s ethos is alive and well in 2016’s Shin Godzilla. As the original film spoke to Japanese trauma after Hiroshima, Hideki Anno’s reboot echoes the tragedy of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and the subsequent nuclear meltdown in Fukushima. In Shin Godzilla, humanity’s vanguard against the unknown is the creaking and corrupt Japanese bureaucracy, who prove woefully inept at managing such an unnatural disaster. We can only look on in horror as the rapidly-mutating Shin Godzilla evolves through a grotesque parody of the history of life, from a flailing tentacle to a hilariously dead-eyed lungfish, then to an armless pseudo-tyrannosaur, and then finally into something that looks less like a kaiju and more like a malevolent walking tumor: at this stage, its flesh blackened and blistered and leaking discharge, it pointedly displays the symptoms of toxic radiation exposure. The movie’s very last shot suggests a final, horrifying metastization that I won’t spoil, but it’s worth noting that Anno’s proposed sequel would evolve the monster further into Lovecraftian territory: first as a shapeless, asexually-reproducing mass of flesh, and then into the realm of the truly cosmic when Godzilla’s internal fusion reactor ignites a miniature big bang inside the creature’s guts.

In Western horror, the dinosaur-as-eldritch-abomination is used to stunning effect in 2020’s “Plague of Madness,” the standout episode of Gendy Tartakovsky’s animated paleo-fantasy Primal. I know some of you will read the phrase “zombie brontosaurus” and roll your eyes, but this thing won a goddamn Emmy Award, so hear me out. “Plague of Madness” opens with an extended, wordless sequence of peaceful sauropods, reminiscent of the animals we see in both The Land Before Time and Jurassic Park: these are gentle giants, and their every movement coveys both tranquility and earth-shaking power. When one of the sauropods contracts a strange disease, the process is agonizing to watch: it sweats, labors to breathe, seeks out water and gulps it down desperately, as pus and mucus start to pool in the contours of its face. The animal suffers intensely, but it does not die, and then quite suddenly— as if compelled to externalize its suffering—it changes from a gentle giant into an entirely different sort of monster. “Plague of Madness” is not a conventional zombie story, as the monster neither cannibalizes its victims nor attempts to spread its infection. Instead, we see an innocent animal possessed by an apparently supernatural force of purposeless, indiscriminate violence. We are witnessing a perversion of the natural order. And it is Tartakovsky’s deliberate use of dinosaur tropes (remember the friendly brachiosaurus in the first Jurassic Park, who sneezes gross dino boogers all over Sam Neill and the kids?) that makes “Plague of Madness” so damnably effective. When the zombronto encounters Primal’s series protagonists, the caveman Spear and his T-Rex companion Fang, the episode shifts gears into a thrilling grindhouse remake of the Sharptooth chase sequences in The Land Before Time. Littlefoot’s Mom finally gets revenge… from beyond the grave!

“At the Mountains of Madness,” Godzilla and Shin Godzilla, Tartakovsky’s Primal; all notable works of paleontological horror. But the final word on the subject, naturally, belongs to the cosmos itself. When I was a little kid, the extinction of the dinosaurs was one of the great historical mysteries; there was growing support for the meteor theory, but scientists had yet to find the proverbial smoking crater. So I was recently quite surprised to learn how, in the innumerable eons since my early childhood, this mystery had been put to rest by a series of remarkable discoveries. Geologists have identified the location of the meteor impact, beneath a shallow sea in the Yucatan Peninsula; physicists have visualized the collision and its aftermath with advanced 3D modeling software; field researchers at the Hell Creek formation in the American Midwest have uncovered the exquisitely-preserved remains of animals that died in the event.

I mentioned earlier that, as a child, I was frequently troubled by recurring images of human extinction. So I cannot overstate how grateful I am that I grew up and out of my dinosaur phase before I was made aware of these discoveries. Because the reality of the K-T extinction event (and I hope you’ll forgive some minor inaccuracies in my account, as the purpose of horror is not the objective representation of reality, but the illustration of realities deformed and distorted in the human imagination): the reality of what happened the day the dinosaurs died was beyond anything my OCD-addled childhood mind could have imagined. And understand, I imagined a lot. A lot. I imagined so many terrible things. This was worse.

* * *

It was a literal mountain. It was bigger than a mountain—in the moment before the impact, in the split-second that its outmost edge made contact with the surface of the earth, its peak was still in the atmosphere. Six miles high. Six miles of solid rock.

It was vaporized on impact.

The earth’s mantle rippled, like someone had tossed a stone into a pond. Not the oceans, I mean the earth’s actual crust: mountains, continents, rippling and cresting and breaking like waves. Rock rippled like water.

Everything within 1,500 km of the crash was just gone. Instantly. Incinerated, not by fire, because fire can’t move that fast, but by a brilliant killing light. Try this: start at the impact crater, on the Yucatan Pennensula, and drive south for 24 hours. You’ll cross the southern Mexican border easily, go through Guatemala, Honduras, maybe make it to Nicaragua if you’re making good time. Every plant and animal within that distance was ash.

After the impact, the wave of displaced earth slowed down, and turned, and began rolling back, crashing back into the crater and then surging upward. Not a volcanic eruption, but the molten earth itself, a charnel tower of liquid rock, rising six miles up in an instant before detonating. Untold tons of ejecta—shards of rock, some as big as your fist—tore into the stratosphere. They circled the earth for about an hour before the first ones started to drop. Tiny meteorites, gaining heat upon reentry.

Across the planet, white-hot glass bullets fell like hail.

On that day, there was an earthquake of a magnitude unseen before or since in the history of terrestrial life. There were mile-high tidal waves. There were volcanic fissures that swallowed entire subcontinents. And still the killing light expanded, crashing into Earth’s atmosphere, and the sky itself began to scream : a shockwave roared through the Americas, a roiling mass of seawater and splintered forests and churning blackened earth and mutilated animals, dead already or dying in agony, a tidal wave of pulp and sewage and gore.

It broke at Hell Creek, in North Dakota. They found ocean-dwelling animals there, corpses borne hundreds of miles inland. They found fish that choked to death on the black ash in their gills. They found animals impaled on each other’s spines.

And as that wave receded, as the last shards of ejecta struck the earth and hissed and cooled, as the fires sputtered (although some would not die out for weeks, even months): the sky went black with ash. A funeral shroud for an immolated world. There would be no direct sunlight, anywhere on earth, for over a decade.

A decade. That’ s only ten years. Not that much time in the greater scheme of things; a blink of an eye, compared to the 200 million years of Mesozoic life that preceded it. But I imagine that was of little comfort to the animals that survived, facing down years of starvation and bone-deep cold in a sunless, smoldering hell.

* * *

So how do you live, then?

How do you live in a world that you know has already ended? How are you supposed carry that burden, that unbearable forbidden knowledge, without falling into madness?

I admit that I’m probably not the best person to ask; I’ve got a pretty bad track record with the “not being driven to madness” thing. If you’re H.P. Lovecraft, it seems the answer is to lock yourself in your house, channel your mortal fear of women and foreigners into stories about octopus monsters, and then die of entirely-preventable colon cancer in your forties because you don’t trust doctors. So that didn’t work out great for him, either.

But maybe we’re just asking the wrong question. Perhaps, instead of struggling to mentally process what we’ve learned about the end of the world, we should look to those who actually lived through it, and try to learn from their actions.

You pop your head out of your den. Safe to forage, as usual; not many predators these days. The great old ones, featherless squamous-skinned giants, are gone. Rats nest in the hollows of their cyclopean skulls; fungi, nourished by their corpses, grasp at the forest’s blighted canopy. Somewhere, beyond the blackened sky, the gibbous moon yet hangs.

You kick at the ashes and dig up some mushrooms and then it’s back to your den, to scatter them amongst your brood: princes of the coal-black ruins, little kings in canary yellow. You preen your proud feathers, your living inheritance, the legacy of your tyrant ancestors. (Is it ironic that, with all those happy herbivorous monsters living in peace in the Great Valley, only the hateful Sharptooth’s descendants endure?) Life finds a way. You may yet survive. If you live, it will be your wings that save you.

* * *

Bibliography

Black, Riley. “Who Wrote the First Dinosaur Novel?” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 8 Dec. 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/who-wrote-the-first-dinosaur-novel-3-13220835/. Accessed 6 Nov 2022.

“The Day the Dinosaurs Died – Minute By Minute.” Youtube. Uploaded by Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell, 15 June 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFCbJmgeHmA. Accessed 8 Nov 2022

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. Trans. Peggy Kamuf. Routledge NY 2006. Pg. 169-70

Dinosaurs: The Final Day with David Attenborough. Produced by Helen Thomas, Narrated by David Attenborough. BBC One, 15 April 2022.

Huxley, Thomas H. “On a Fossil Bird and Fossil Cetacean from New Zealand.” Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, Volume 15, pp. 670 – 677. Accessed 6 Nov 2022.

Lovecraft, H. P. “At the Mountains of Madness.” Astounding Stories, Feb-Apr. 1936. https://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/fiction/mm.aspx. Accessed 14 Nov 2022.

Preston, Douglas. “The Day the Dinosaurs Died.” The New Yorker, 29 Mar. 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/04/08/the-day-the-dinosaurs-died. Accessed 7 Nov 2022.

Savile, Frank. Beyond the Great South Wall: The Secret of the Antarctic. New Amsterdam Book Company, 1901. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/66187/pg66187-images.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2022

Simpson, George Gaylord. “Fossil Penguins.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume 87, pp. 1-100, August 8, 1946. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/bitstream/2246/392/1/B087a01.pdf. Accessed 24 Oct 2022.

Fletcher Wortmann is the author of Triggered: A Memoir of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, (Thomas Dunne Books, 2012) and an ongoing columnist for Psychology Today. He writes about mental health and abnormal psychology from an irreverent, autobiographical perspective, which often draws on his lifelong love of sci-fi and fantasy fiction.

[1]Huxley, “On a Fossil Bird and Fossil Cetacean from New Zealand.”

[2]Simpson, “Fossil Penguins.”

Great piece. I was going to quibble with “the dinosaurs are all gone now” on the grounds that we just call the survivors’ descendants something else now, but you get there in the end.

If you want to take that cosmic horror to the next level, how about the way they did it in Chrono Trigger: what if that thing that fell wasn’t just a rock? What if it had a life cycle of its own, and its spawn will one day emerge to ruin the surface all over again? What would you do to stop that next apocalypse, if you could?

The actual dinosaurs that show up in Chrono Trigger are mere beasts by comparison. Sure, they might try to eat you, but only in a mundane and understandable way.

P.S. Compared to your description the 65Mya event in CT is MUCH smaller, but IDK if that’s more of an intentional artistic decision or just that a lot of the research you’re referring to hadn’t been done yet.

Great article. I particularly liked the “charnel tower”.

Douglas Henderson wrote and illustrated a book on the K/T impact – Asteroid Impact. Very vivid images of what it must have been like. Probably just as well you didn’t see it as a child, Fletcher.

Incidentally, as someone who spent the summer going through the systematic literature on a lizard group, from Linnaeus to the present, I found your literature dive into the giant penguin question quite refreshing.

This was the most intriguing, mind-grabbing article I’ve read in YEARS. Bravo, sir. Bravo!

Very interesting article, especially the giant penguins!

Great descriptions of the meteor and its aftermath. If you’re interested in further reading, I think the best book which covers this is The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs by Steve Brusatte.

Why were the Pizza Hut puppets “hideous”? They looked exactly like the cartoon characters.

Fantastic article.

I became obsessed with dinosaurs decades before The Land Before Time and while I recognized their extinction it wasn’t what I focused on. My horror was that we weren’t there – people, in any way, shape, or form, didn’t exist. None of my ancestors had a pet dinosaur like Fred Flintstone’s Dino. It was our impermanence that kept me up at night.

I like the dinosaur book/ Necronomicon comparison. Perhaps it should be Dinonomicon?

Lovecraft does seem to have kept abreast of the latest scientific findings to exploit them for his fiction. I think he might have the distinction of being among the first science fiction writers to incorporate the discovery of Pluto.

Outstanding article! Intrigue, suspense, and science! Thank you for such a fun read, I’ll be dwelling on this for days!

See also The Last Days of the Dinosaurs by Riley Black. An extremely vivid account about what it might have been like at Hell Creek, Montana, beginning just before the impact, and then in the first hour, month, and day afterwards, in absolutely horrifying detail. The chapters then progress to the next month, the next year, and then 100 years, 1,000 years, 100,000 years, and 1 million years later. It’s a dizzying journey through geologic time. The author has an uncanny way of depicting how the creatures who lived and died might have reacted to what was happening, and how those that survived managed to adapt (or not) to a horribly changed world.

66 million years ago, but I take your point. Also, Mufasa and Bambi’s mum have nothing on Littlefoot’s mother. Seriously, even as an adult, I can’t bring myself to rewatch TLBT because of that. I know what it’ll do to me :'(

@1 Birds are dinosaurs only in the sense that they are also fish. It is true by certain definitions, but not by others.

I loved it.

@10 It’s 66My ago? I remember when it was 65My. I must be getting old.

(And in other reminders: Shania Twain in Beauty and the Beast is older than Angela Lansbury, the Sex In The City girls are older than The Golden Girls, and Wesley Crusher is older than Picard.)

great interesting article. thanks

Great essay. I would quibble with your assertion that the “dinosaur boom” started in the 1980s and 90s, based on my own personal experience. I was obsessed with dinosaurs as a kid in the early 1960s. I still have my Time-Life dinosaur picture books, and there were lots of stop-motion dinosaurs in the sci fi movies I watched on Saturday afternoons (movies like the Lost World), not to mention the dinosaur-filled world of The Flintstones. I remember seeing giant animated dinosaurs at the 64/65 world’s fair in NYC, and getting an injection molded brontosaurus at one of the oil company booths that were promoting the use of plastics. And I can’t really remember a time in my life when dinosaurs were not a part of popular culture.

Best digression ever

I’m a little puzzled as to how these phrases indicate huge height “…in the split-second that its outmost edge made contact with the surface of the earth, its peak was still in the atmosphere.” I mean, when I’m taking a walk, every split-second that my foot touches the ground the top of my head is still in the atmosphere. And I’m not actually very tall. I’m thinking some other word than “atmosphere” is wanted here? Or maybe “its peak is still beyond the atmosphere”?